The Heart of Modern Aviation

Jet engines convert chemical energy into mechanical thrust. That’s it. Everything else is engineering detail.

Every commercial airliner you see operates with jet engines. Boeing 737s. Airbus A380s. Regional jets. Business jets. All powered by controlled explosions happening thousands of times per minute.

The basic principle hasn’t changed since Frank Whittle and Hans von Ohain independently invented the jet engine in the 1930s. Modern engines just do it better – quieter, more efficient, more reliable.

Modern aircraft like the Boeing 787 and Airbus A350 rely on advanced turbofan engines delivering 20-30% better fuel efficiency than previous generations. These engines power aircraft across oceans, through weather, at altitudes where humans can’t survive.

This guide explains how jet engines work, from basic principles to technical details.

What Is a Jet Engine? (Basic Definition)

A jet engine is a reaction engine that generates thrust by accelerating air backward.

Newton’s Third Law: For every action, there’s an equal and opposite reaction. Jet engines push air backward at high speed. Aircraft moves forward. That’s thrust.

No magic. No mystery. Just physics.

Key concept: Jet engines don’t push against anything external. They accelerate mass (air) backward. The reaction force pushes the aircraft forward. This works in thin air at 40,000 feet just as well as at sea level.

Unlike piston engines with propellers (which have mechanical limits around 400 mph), jet engines operate efficiently at speeds exceeding 500 mph. This makes them ideal for commercial aviation.

Main Types of Jet Engines

Four main types power aircraft today. Each suits different missions.

Turbojet (Original Design):

Oldest jet engine configuration. All air passes through engine core. Simple concept but inefficient and extremely loud.

Military fighters still use turbojets or low-bypass turbofans for supersonic flight. Commercial aviation abandoned pure turbojets decades ago due to fuel consumption and noise.

Turbofan (Dominant Today):

Most common jet engine on commercial aircraft. Large fan at front moves massive amounts of air. Most air bypasses engine core.

Modern turbofans power everything from regional jets to widebody aircraft. Quiet operation. High efficiency. Proven reliability.

Turboprop:

Jet engine driving a propeller through gearbox. Efficient at speeds below 400 mph and altitudes under 25,000 feet.

Regional airlines use turboprops for short flights. Examples: ATR 72, Bombardier Q400. Lower fuel consumption than jets at low speeds. The ATR72, ATR42 and Q400 demonstrate how turboprop efficiency suits regional operations under 500 miles.

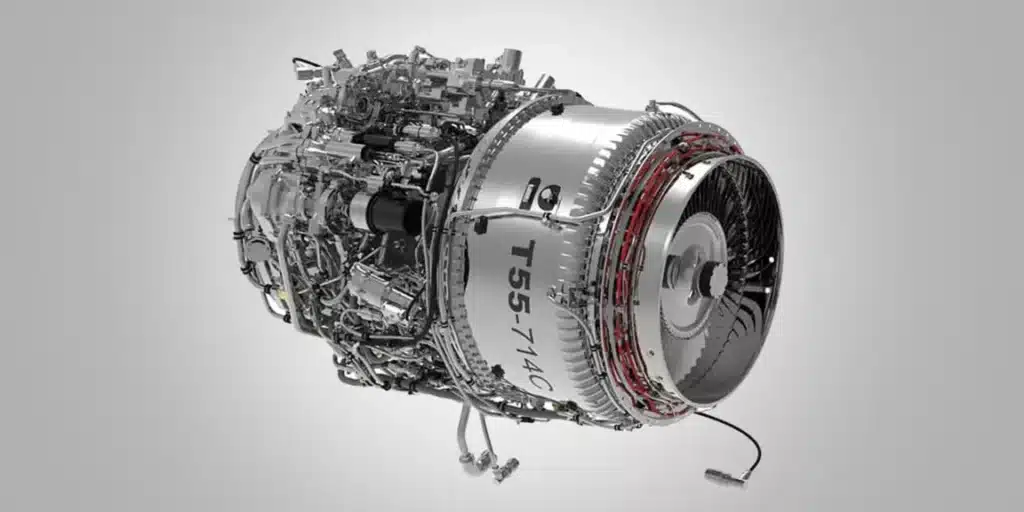

Turboshaft:

Jet engine optimized for shaft power instead of thrust. Powers helicopters and some ground equipment.

Extracts maximum energy to drive rotor system. No thrust nozzle needed.

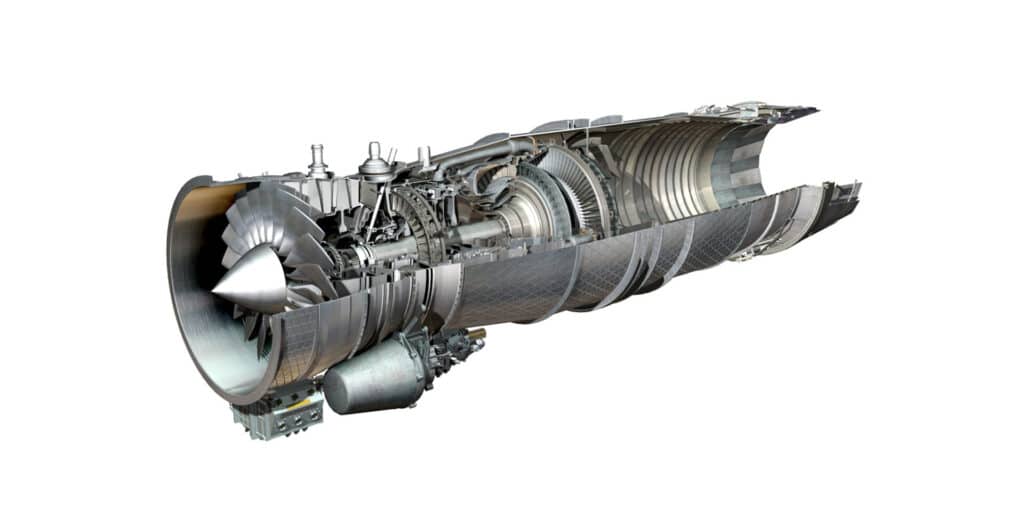

How a Turbofan Jet Engine Works (Step-by-Step)

Modern turbofan engines dominate commercial aviation. Understanding turbofans means understanding how almost all airliners fly.

Step 1: Air Intake

Air enters engine through inlet at aircraft’s flight speed. Could be 250 mph during climb or 550 mph at cruise.

Inlet design slows incoming air to around 350 mph before it reaches the fan. Too fast and compressor blades stall. Proper airflow management matters.

Engine inlets on commercial aircraft are carefully shaped to handle various flight conditions – takeoff, climb, cruise, descent. Computational fluid dynamics helps engineers optimize inlet geometry.

Step 2: Fan (Bypass Air)

Large fan at engine’s front dominates what you see from outside aircraft. Fan diameter ranges from 61 inches (regional jets) to 134 inches (GE9X on Boeing 777X).

Fan accelerates incoming air. Two paths exist:

Bypass air: 80-90% of air flows around engine core through bypass duct. This air never enters combustion chamber. Fan acceleration alone generates most thrust in modern engines.

Core air: 10-20% of air enters engine core for compression, combustion, and turbine operation.

Bypass ratio determines engine efficiency. Higher bypass ratio means better fuel economy and quieter operation. Modern engines achieve bypass ratios of 9:1 to 12:1. Some future designs target 15:1 or higher.

Step 3: Compressor

Core air enters compressor section. Multiple stages of rotating blades squeeze air progressively.

Commercial engines use 8-14 compressor stages. Each stage increases pressure. Total pressure rise ranges from 30:1 to 50:1 depending on engine design.

Compressing air raises temperature. Air entering combustor already reaches 600-900°F before fuel ignition. This pre-heating improves combustion efficiency.

Why compression matters: Higher pressure enables more complete fuel burning and extracts more energy per pound of fuel. Thermodynamic efficiency improves with compression ratio.

Step 4: Combustion Chamber

Compressed air enters combustion chamber where fuel injection and ignition occur.

Fuel injectors spray kerosene (Jet A or Jet A-1) in fine mist. Air-fuel mixture ignites and burns continuously. Once started, combustion self-sustains – no spark plugs needed during normal operation.

Combustion chamber temperatures reach 3,000-3,600°F. Special cooling techniques protect metal components. Only about 25% of air entering combustor participates in burning. Remaining air cools combustion products and chamber walls.

Aviation fuel properties affect combustion efficiency and engine performance. Different fuel grades serve different purposes – commercial aviation uses Jet A-1 primarily for its consistent freezing point of -47°C.

Step 5: Turbine

Hot, high-pressure gases exit combustor and hit turbine blades. Turbine extracts energy from gas stream.

Turbine blades spin at 10,000-15,000 RPM depending on engine size. These blades operate in temperatures exceeding their melting point. Internal cooling passages and ceramic coatings enable survival.

Energy extracted by turbine powers the compressor and fan at engine’s front. Turbine and compressor connect via shaft (actually multiple concentric shafts in modern engines).

Critical balance: Turbine must extract enough energy to drive compressor and fan, but not so much that insufficient energy remains for thrust generation.

Step 6: Exhaust and Thrust

Remaining energy exits through exhaust nozzle as high-velocity gas. Core exhaust velocity reaches 1,200-1,500 mph.

But here’s the key detail most people miss: Core exhaust generates only 20-30% of total thrust in modern turbofans. The fan’s bypass air produces 70-80% of thrust.

This distribution makes modern engines dramatically quieter than older designs. Slower-moving air (bypass) generates less noise than supersonic core exhaust.

Where Does the Thrust Actually Come From?

Common misconception: Jet engines work by shooting hot exhaust backward.

Reality: Modern turbofans generate most thrust from bypass air accelerated by the fan.

Thrust breakdown in typical modern turbofan:

Fan (bypass air): 75-80%

Core exhaust: 20-25%

Why this matters: Higher bypass ratios mean more thrust from relatively slow-moving air (900-1,100 mph) rather than supersonic core exhaust (1,200-1,500 mph). This improves fuel efficiency and reduces noise dramatically.

Think of it as moving large mass slowly versus small mass quickly. Both produce thrust through momentum change. Large mass slowly wins for efficiency.

Old turbojets had zero bypass. All thrust came from core exhaust. Loud, inefficient, but simple. Modern turbofans sacrifice simplicity for massive efficiency gains.

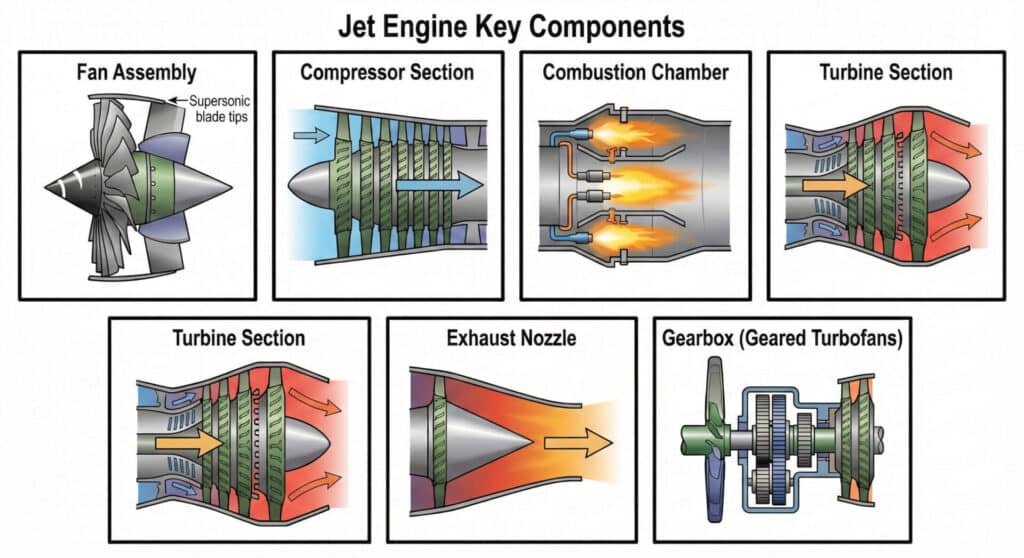

Key Components of a Jet Engine

Six major components define turbofan architecture:

Fan Assembly:

Front-mounted fan with 18-24 blades depending on size. Made from titanium or composite materials. Drives bypass airflow.

Fan blade tips reach supersonic speeds (over 1,000 mph) during takeoff. Special aerodynamic design prevents shock waves that would reduce efficiency.

Compressor Section:

Multiple stages of rotating blades (rotor) and stationary vanes (stator). Progressively compresses air entering engine core.

Modern engines split compressor into low-pressure and high-pressure sections rotating at different speeds. This improves efficiency across operating range.

Combustion Chamber:

Annular chamber surrounding engine centerline. Fuel injectors, igniters, and cooling systems maintain continuous combustion.

Modern combustors use advanced materials and cooling techniques to operate at extreme temperatures while meeting emissions regulations.

Turbine Section:

Multiple stages of blades extracting energy from hot gas stream. High-pressure turbine drives compressor. Low-pressure turbine drives fan.

Turbine blades represent peak materials science. Single-crystal superalloys with internal cooling passages enable operation at temperatures exceeding blade melting point.

Exhaust Nozzle:

Fixed or variable-geometry nozzle accelerating core exhaust to final velocity. Most commercial engines use fixed nozzles. Military engines often use variable nozzles for performance optimization.

Gearbox (Geared Turbofans):

Some modern engines use gearbox between fan and low-pressure turbine. Allows fan and turbine to rotate at different optimal speeds.

The Pratt & Whitney PW1000G pioneered geared turbofan technology in commercial aviation. Gearbox enables fan to rotate slower than turbine, improving efficiency by 15-20% compared to direct-drive engines.

What Is Bypass Ratio (And Why It Matters)?

Bypass ratio defines modern jet engine performance. Simple definition: mass of air flowing through bypass duct divided by mass flowing through engine core.

Example calculations:

Low bypass (military): 0.5:1 to 2:1

Medium bypass (older commercial): 4:1 to 6:1

High bypass (modern commercial): 9:1 to 12:1

Ultra-high bypass (future): 15:1 to 20:1

Why higher bypass improves efficiency:

Moving larger mass of air slowly requires less energy than moving small mass quickly for same thrust. Physics favors high bypass for subsonic flight.

Propulsive efficiency formula shows this mathematically. Higher bypass ratios approach propeller efficiency while maintaining jet speed capability.

Noise reduction:

Higher bypass ratios reduce noise significantly. Bypass air at 900 mph produces far less noise than core exhaust at 1,400 mph. This matters for airport noise regulations.

Trade-offs:

Higher bypass means larger, heavier engines. Engine diameter increases. Nacelle drag increases. At some point, benefits plateau. Current technology optimizes around 10:1 to 12:1 for widebody aircraft.

The Airbus A320neo family demonstrates high-bypass turbofan benefits – 15% better fuel efficiency than previous generation while meeting strict noise requirements at European airports.

How Jet Engines Start and Keep Running

Jet engines don’t start themselves. They need help initially. Once running, they’re self-sustaining.

Ground Start Sequence:

Step 1: External power source (APU bleed air or ground cart) spins engine core to 15-20% RPM.

Step 2: Fuel flow begins when rotation speed sufficient for stable combustion.

Step 3: Igniters (similar to spark plugs) create sparks in combustion chamber.

Step 4: Fuel ignites. Combustion begins.

Step 5: Rising temperature and pressure accelerate turbine. Engine self-accelerates to idle RPM (typically 60-70% of maximum).

Step 6: Igniters turn off. Combustion self-sustains.

Entire sequence takes 60-90 seconds from start command to stable idle.

In-Flight Restart:

If engine shuts down during flight, windmilling from forward airspeed provides rotation. Pilot restores fuel flow and ignition. Engine typically restarts within 30 seconds if conditions permit.

FADEC Control:

Full Authority Digital Engine Control manages modern engines. Dual-channel computer controls fuel flow, variable geometry, and monitors thousands of parameters.

FADEC prevents pilot from over-temping, over-speeding, or damaging engine. Computer manages precise fuel scheduling for optimal performance at all altitudes and temperatures.

Pilots interact with throttle lever. FADEC translates throttle position into specific N1 target (fan speed). Computer handles everything else.

Why Jet Engines Are So Efficient at High Altitude

Jet engines improve efficiency as altitude increases. Opposite of what intuition suggests.

Thinner Air Reduces Drag:

Air density at 40,000 feet is one-quarter sea level density. Aircraft drag drops proportionally. Less thrust needed to maintain speed.

Temperature Matters:

Cold air at altitude (-40°F to -70°F) is denser for given pressure. Compressor works more efficiently with cold air. More oxygen molecules per cubic foot means better combustion.

Optimized Operating Point:

Engines are designed for cruise conditions at 35,000-43,000 feet. Compression ratios, turbine temperatures, and bypass ratios all optimize around this altitude range.

At sea level, engines operate below design point. Plenty of power but not maximum efficiency. At cruise altitude, engines hit sweet spot.

True Airspeed vs Indicated Airspeed:

Thin air enables higher true airspeeds for same thrust. Aircraft flies at 450-500 knots true airspeed at altitude. Equivalent indicated airspeed might be 250-280 knots. Engine provides thrust based on indicated values, but aircraft moves fast through actual air.

This altitude advantage explains why airlines cruise at 35,000+ feet. Fuel efficiency improves 15-20% compared to low-altitude flight.

Jet Engine Fuel – What Do They Burn?

Commercial jet engines burn kerosene-based fuel. Two main types exist worldwide.

Jet A: Primary fuel in United States. Freezing point -40°C (-40°F).

Jet A-1: International standard fuel. Freezing point -47°C (-53°F). Lower freezing point enables polar routes.

Chemical composition similar to diesel fuel. Kerosene fractions from crude oil distillation. Energy density around 43 MJ/kg.

Why Freezing Point Matters:

Fuel tanks in wings experience extreme cold at cruise altitude. Fuel temperature drops to -40°C or below. Jet A would gel on polar routes. Jet A-1 remains liquid.

Critical Properties:

Energy density (thrust per pound)

Flash point (safety)

Viscosity (pump-ability at low temp)

Freezing point (operational limits)

Thermal stability (heat absorption capability)

Jet fuel also serves as hydraulic fluid and coolant in fuel-cooled oil coolers. It’s not just energy source.

Sustainable Aviation Fuel:

SAF adoption increases gradually. Current SAF chemically identical to conventional jet fuel but derived from sustainable sources like used cooking oil, agricultural waste, or synthetic processes. The growing adoption of SAFs shows airlines committing to emissions reduction despite higher fuel costs.

Airlines can blend up to 50% SAF with conventional fuel without engine modifications. 100% SAF approval progressing but requires extensive testing.

Are Jet Engines Safe?

Modern jet engines achieve remarkable safety records through redundancy, testing, and regulation.

Certification Requirements:

FAA and EASA require engines to demonstrate safety through extensive testing:

Ingestion tests: Engines must ingest birds, ice, and debris without uncontained failure.

Bird strike: Engines must survive 4-pound bird at cruise speed or multiple smaller birds.

Blade-off test: If fan blade breaks, containment ring must prevent it from penetrating engine cowling.

Redundancy:

Twin-engine aircraft can fly, maneuver, and land on one engine. Extended-range Twin Operations (ETOPS) certification allows twin-engine aircraft on routes up to 370 minutes from nearest airport.

Modern engines achieve in-flight shutdown rates below 1 per 100,000 flight hours. Uncontained failures (most serious) occur less than 1 per million flight hours.

Fire Protection:

Fire detection and suppression systems monitor engine and nacelle. Automatic systems plus pilot-activated fire bottles provide multiple protection layers.

Real-World Reliability:

Commercial engines operate 25,000-50,000 hours between major overhauls. Some engines exceed 100,000 hours total life. This reliability comes from conservative design, quality manufacturing, and strict maintenance protocols.

Future of Jet Engines (2026-2040)

Engine technology continues evolving. Several trends shape next 15 years.

Ultra-High Bypass Ratios:

Next-generation engines target bypass ratios of 15:1 to 18:1. GE and Rolls-Royce develop designs with even larger fans. Challenge: engine diameter and nacelle drag limits.

Open rotor concepts eliminate nacelle entirely. Visible fan blades rotate in open air. 20-30% efficiency improvement possible but noise and certification challenges remain.

Geared Turbofan Expansion:

Pratt & Whitney’s geared turbofan proved successful. Competitors develop similar architectures. Gearbox enables fan to rotate at optimal speed independent of turbine.

The PW1100G geared turbofan demonstrates 16% fuel burn reduction and 75% noise footprint reduction compared to previous generation engines.

Advanced Materials:

Ceramic matrix composites (CMC) replace metal in hot sections. CMCs tolerate higher temperatures while weighing less. This enables higher turbine inlet temperatures and better efficiency.

GE’s GE9X already uses CMC components. Future engines will expand CMC usage throughout hot sections. The Airbus A330neo and Boeing widebody competitors showcase how modern engine technology directly impacts aircraft economics.

Additive Manufacturing:

3D printing enables complex internal cooling passages impossible with conventional manufacturing. Weight reduction and performance improvement both benefit.

GE produces fuel nozzles via additive manufacturing – single printed part replaces 20 traditionally-manufactured components.

Hybrid-Electric Concepts:

Electric motors assist during high-power phases (takeoff, climb). Batteries or generators supplement jet engine. Benefits include reduced noise during departures and improved efficiency.

Small aircraft may achieve hybrid-electric within 10 years. Large commercial aircraft face battery energy density limitations for decades.

Sustainable Fuel Compatibility:

All new engine designs must handle 100% SAF eventually. Drop-in compatibility with existing fuel infrastructure remains priority.

Synthetic fuels and hydrogen receive research attention but face massive infrastructure challenges. Kerosene-based SAF offers near-term emissions reduction without fleet replacement.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do jet engines produce thrust?

Jet engines accelerate air backward using a fan and core exhaust. Newton’s Third Law creates forward thrust equal to momentum change of air. In modern turbofans, 75-80% of thrust comes from bypass air moved by the fan, not from core exhaust.

Do jet engines suck in air or push it out?

Both. The fan and compressor pull air into the engine. The turbine and exhaust push air out at higher velocity. Net effect: mass of air accelerated backward produces forward thrust.

What fuel do jet engines use?

Commercial jets use kerosene-based fuel called Jet A (US) or Jet A-1 (international). Jet A-1 has lower freezing point (-47°C) enabling polar routes. Military jets use JP-8 (similar to Jet A-1) or JP-5 (naval aviation with higher flash point).

Why are jet engines loud?

Noise comes primarily from high-velocity exhaust mixing with ambient air and fan blade tip speeds. Core exhaust exits at 1,200-1,500 mph, creating shear layers that generate sound. Modern high-bypass engines reduced noise dramatically by generating thrust with slower-moving bypass air rather than supersonic core exhaust.

Can a jet engine run without fuel?

No. Jet engines require continuous fuel flow to maintain combustion. If fuel flow stops, combustion ceases and engine winds down. Windmilling (rotation from airflow) continues during flight but produces no power. Pilots can attempt in-flight restart by restoring fuel flow and ignition.

What happens if a jet engine fails?

Modern twin-engine aircraft can fly safely on one engine. Performance degrades – lower climb rate, reduced cruise speed, decreased range – but aircraft can reach alternate airport and land normally. Pilots train extensively for single-engine operations. Engine failure is rare (less than 1 per 100,000 flight hours).

Why do jet engines have big fans?

Larger fans move more air. Moving large mass of air slowly produces thrust more efficiently than moving small mass quickly. High bypass ratio (9:1 to 12:1) improves fuel efficiency by 15-30% compared to older low-bypass engines. Larger fans also reduce noise by generating thrust with slower-moving air.

How hot does a jet engine get?

Combustion chamber temperatures reach 3,000-3,600°F (1,650-2,000°C). Turbine inlet temperature (immediately after combustor) operates at 2,500-3,000°F. Turbine blades withstand temperatures exceeding their melting point through internal cooling passages and ceramic coatings. Exhaust gas exits around 800-1,200°F depending on throttle setting.

Why do jet engines work better at high altitude?

Thin air at cruise altitude (35,000-43,000 feet) reduces aircraft drag by 75% compared to sea level. Cold temperatures (-40°F to -70°F) improve compressor efficiency. Engines are designed to operate optimally at these conditions. Combined effect: 15-20% better fuel efficiency at cruise altitude versus low altitude flight.

What is the lifespan of a jet engine?

Commercial jet engines operate 25,000-50,000 hours between major overhauls. Total engine life can exceed 100,000 hours across multiple overhaul cycles. Modern engines achieve 50,000+ flight hours before first overhaul. Maintenance schedules follow flight hours, cycles (takeoff/landing), and calendar time.

Authors

-

Radu Balas: Author

Pioneering the intersection of technology and aviation, Radu transforms complex industry insights into actionable intelligence. With a decade of aerospace experience, he's not just observing the industry—he's actively shaping its future narrative through The Flying Engineer.

View all posts Founder

-

Cristina Danilet: Reviewer

A meticulous selector of top-tier aviation services, Cristina acts as the critical filter between exceptional companies and industry professionals. Her keen eye ensures that only the most innovative and reliable services find a home on The Flying Engineer platform.

View all posts Marketing Manager

-

Marius Stefan: Editor

The creative force behind The Flying Engineer's digital landscape, meticulously crafting the website's structure, navigation, and user experience. He ensures that every click, scroll, and interaction tells a compelling story about aviation, making complex information intuitive and engaging.

View all posts Digital Design Strategist